| |

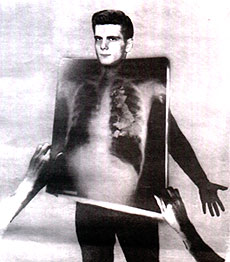

TB, that

‘quiet and solemn struggle between soul and

body’, is on the rise again, NIGEL HAWKES reports

For

a century or more, a pilgrimage of death saw thousands

of English consumptives making their painful journey

to Pan, a small French town in the shadow of the

Pyrenees. Here, they believed, a climate of tranquillity

could free them from a disease that already had

them by the throat.

The winter trees in Pan might

tremble, but they would never shake. The town

was calm, its gardens handsome, its air as still

as a shroud. To generations raised in the belief

that wind, chill and the bustle of cities were

the enemies to be avoided, Pan represented hope.

It is easy to mock the false

expectations, but impossible not to be moved by

the hopes that Pan inspired. Tuberculosis was

a terror without class distinction. Nobody knew

how it was caused, how it chose its victims. When

a lifebelt is nowhere to be found, grasping at

a straw makes a kind of sense.

Professor Charles Louis,

France's leading TB expert in the 1840s, married

late. When TB struck down his only son, Louis

gave up his career and went to live with him in

Pan. He did not believe that a change of climate

could effect a cure, and never changed his mind.

But he went on hoping against belief, a mental

contortion of the kind TB imposed even upon the

most rational. His son soon died.

In

the first half of the 19th Century there was hardly

a person in London who was not infected with TB.

But while infection was universal, the disease

was not. Even though it was the principal cause

of death in Europe and much of North America,

its incidence had an arbitrariness that puzzled

even the cleverest physicians.

We now know that TB is caused

by a bacillus, a rod-shaped bacterium first isolated

by the German Robert Koch in 1882. But not all

those who carry the bacillus develop the disease.

In an era when everybody was exposed to TB it

was perfectly sensible to believe that the disease

was hereditary, since what determines illness

in such circumstances is genetics. If everybody

carries a germ but only a proportion succumb,

then it is the genes that pick losers from winners.

In 1837 the English physician

Sir James Clerk listed "improper diet, impure

air, deficient exercise, excessive labour, imperfect

clothing, want of cleanliness, abuse of spirituous

liquors, mental causes and contagion" as

the causes of consumption. The germ came last

in Sir James' catalogue.

|

| 1936: At St. Thomas' hospital,

TB patients take to the open air |

His contemporary, the American

physician William Beach, dismissed contagion altogether,

emphasising instead hereditary disposition"

marked by such features as a narrow chest or prominent

shoulders. Beach recommended travel, sending a

few more American consumptives to the grand hotels

of Pan and others to Brazil and the West Indies.

Beach was wrong, but so perhaps

were those who saw Koch's discovery as "the

last word on the subject". The historiography

of TB is split by a long-running and fascinating

dispute over how it came to be conquered, a dispute

that is of more than merely historical interest

now that TB is on the march again.

If the bacillus is the villain,

then it is the sulphonamides and, later, the antibacterials

that are the heroes of the TB story. By identifying

a germ, Koch set in train the process that in

due time produced the magic bullets to destroy

that germ, and eliminate the disease.

But the paradox is that TB

was on the wane by the time the magic bullets

arrived. It had been in steady - indeed, precipitate

- decline since the 1840s, for reasons still argued

over. The historian Thomas McKeown has claimed

that TB and other infectious diseases declined

not as a result of medical interventions but in

consequence of social and economic changes.

"Effective clinical

intervention came late in the history of the disease,

and over the whole period of its decline the effect

was small in relation to that of other influences,"

he said. Better nutrition was the key, according

to this view.

One could equally argue that

the germ itself had changed, or that better public

hygiene and the isolation of infective TB patients

had made the difference. The fact remains that

TB was on the way to being conquered before doctors

had the weapons to which their victory is now

attributed. Other nightmare diseases have seen

a similar rise and fall in incidence: today the

parallel is with heart disease, whose decline

is difficult to explain by the dietary theories

supposed to be its cause.

Misunderstanding what put

paid to TB is a major part of the problem we have

with the disease today. The theory that drugs

had conquered infection had only brief prominence,

from about 1960 to the appearance of HIV infection

in the early 1980s, but most of today's doctors

took it in with their mothers' milk. What was

overlooked was the germ's capacity to change in

response to a new environment, and its ability

to prey on those weakened by AIDS, poverty and

neglect. To have ignored some of these things

required averting the gaze from what has been

going on in the Third World, but we are well practised

in that art. It was much easier to see the rise

of TB among the poor as the failure of governments

to deliver the drugs needed to control it.

|

Compliance - or the lack

of it - became the World Health Organisation's

watchword, its policy one of directly observed

therapy, or standing over people making sure they

took their pills. There is nothing wrong with

this, as far as it goes. But curing even a standard

case of TB requires compliance over many months,

and drug-resistant TB is a tougher problem still.

Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) can be treated,

but only at huge cost.

In New York, where valiant efforts have been made

to get MDR-TB under control, management of a single

case can cost US$250,000. In Russian prisons,

where TB is rife, a fifth of all cases - some

say two fifths - are estimated to be MDR-TB.

Nor has the rise of TB left

its old stamping ground untouched. The teeming

slums of London in the 19th Century provided an

ideal culture medium for multiplying TB. Today,

London is much cleaner and less crowded, but TB

infections are nevertheless on the rise once more.

The rate of infection in Newham, at 100.6 per

100,000, is now greater than it is in Uzbekistan

(94 per 100,000) or Azerbaijan (82).

The whole of this increase

can be accounted for by the poorest 30 per cent

of society, especially those who live in crowded,

ethnically diverse communities where immigration

is a major source of new infection. The rich have

as yet no need to fear TB as they once did, but

the rise in cases has not yet elicited the kind

of response in London that turned the tide in

New York.

Nor has basic protection against TB been stepped

up. While cases have been rising, vaccination

has fallen, from 742,000 in 2001-02 to only 450,000

in 2002-03. The risk of catching TB in the shires

may still be very low, but there is little evidence

of any concerted effort to keep it that way. Like

doctors, ministers seem locked in a simplistic

model of how TB was conquered, and persistently

make public health a far lower priority than efforts

to improve hospital care or deliver drugs.

But the real lesson of TB

is more profound than quibbling about whether

the British government, or any overnment, is doing

enough to deal with it. Rather, as Alimudden Zumla

and Matthew Gandy argue in a new book, The Return

of the White Plague, it is a question of explaining

how a deadly disease that has a cheap and effective

cure remains the leading cause of death and disability

worldwide.

This is, they insist, a medical

failure. How can it be that in 1993, more than

50 years after the development of effective treatments,

the World Health Organisation was forced to declare

TB a global emergency?

This is, said Charles Dickens,

"a dread disease, in which the struggle between

soul and body is so gradual, quiet and solemn,

and the result so sure, that day by day and grain

by grain the mortal part withers away, so that

the spirit rows light and sanguine with its lightening

load and, feeling immortality at hand, deems it

but a new term of mortal life - a disease in which

death takes the glow and hue of life, and life

the gaunt and grisly form of death".

That is the kind of prose

we need to wake us to a threat that once sent

thousands to die in Pan. We conquered TB once;

now we need to do it again.

- The Times |

|